Color has always been something longed for since the dawn of cinema. In an era when moving images were only available in stark black and white, the world of film was filled with captivating shades of gray and sharp shadows, yet it was unable to fully convey the warmth of the sun, the softness of dusk, or the depth of night. While monochrome imagery offered its own form of dramatic impact, it remained limited in conveying emotional nuances.

From this limitation arose the desire to introduce color—not merely to enhance beauty, but as a bridge to emotion. This desire continued to evolve through various technical and artistic experiments. Ultimately, this visual element became an integral part of how we experience and understand film.

Manual Coloring: The Beginning of Imaginative Sensitivity

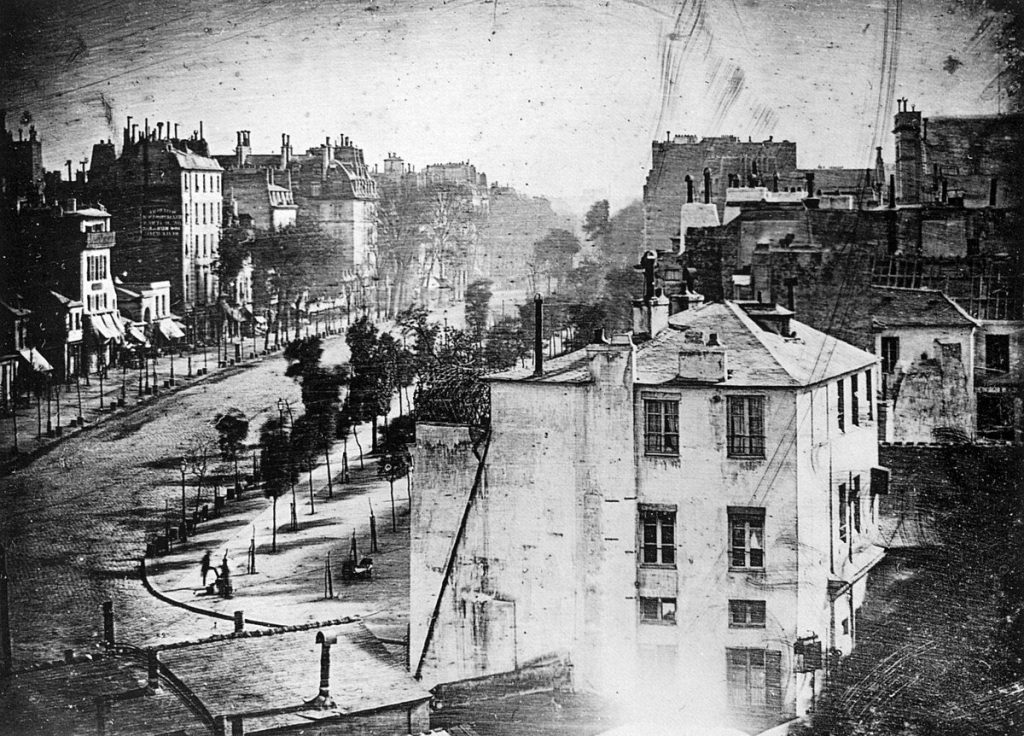

Before film knew the full spectrum, photographers had already attempted to add color to images. In 1842, Johann Baptist Isenring from Switzerland experimented with coloring daguerreotypes—the ancestors of modern photography—with pigments attached using gum arabic. The process was lengthy, the results easily faded, but it was enough to make people realize that color could add emotional depth. This experiment paved the way for a more vibrant visual approach.

As cinema flourished in the early 20th century, films were still presented in grayscale. However, filmmakers wanted something more. Due to the limitations of technology at the time, they resorted to manual coloring techniques such as tinting and toning.

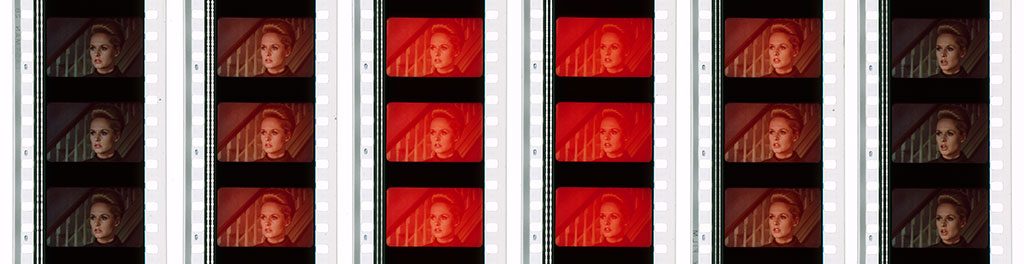

Tinting involved immersing the entire film reel in a special solution, creating a mood through a dominant color palette—blue for night, vibrant red for fire, and yellow for morning light. Meanwhile, toning replaced the dark areas of an image with a specific hue, producing a unique contrast effect. These techniques were used in major works such as The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Metropolis (1927), adding an extra layer of expressiveness to every frame.

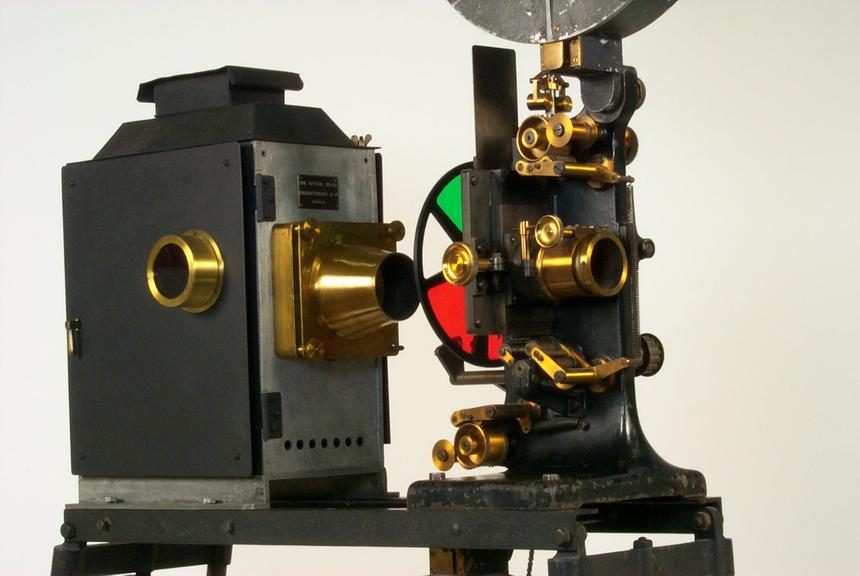

In 1906, George Albert Smith and Charles Urban introduced Kinemacolor, the first system to successfully capture the spectrum mechanically. This technology used two filters—red and green—that recorded images alternately, then projected them with synchronized lighting. The results were not yet perfect: sometimes lines or blurry images appeared. However, for audiences of that time, witnessing the world move with different hues was an extraordinary experience. This system proved that a nuanced approach was no longer a dream but a reality beginning to take shape. Despite its popularity waning by 1914.

In 1932, Technicolor Corporation launched their three-strip system. Using red, green, and blue filters, this technology recorded with greater precision. Its debut in Becky Sharp (1935) marked a new era in cinema history. Films like Gone with the Wind (1939) and The Wizard of Oz (1939) demonstrated how visual palettes could become powerful narrative elements.

However, this technology was expensive and complicated. So in the early 1950s, Eastman Kodak introduced Eastmancolor, a more practical single-strip system. Although not as sharp as the previous system, its efficiency led major studios to switch to it. It didn’t take long for this method to become the industry standard and end the era of three-strip.

Digitization and the Colorization Controversy

The 1980s marked the emergence of a new controversy. Hal Roach Jr. founded Colorization, Inc. and began converting classic black-and-white films into color versions through a digital process. Films such as Topper (1937) were re-released with a new look. However, strong reactions emerged.

Critics like Roger Ebert condemned this move as a violation of the director’s vision. The composition of light and shadow was deemed disrupted, and the original feel of the film was altered. Despite technological advancements, the debate over artistic authenticity persists.

Today, the use of color in films is not just about aesthetics. It has become its own language for conveying emotions: red reflects passion or anger, blue evokes loneliness, green holds mystery, and yellow brings warmth. Filmmakers work with great detail, from the planning stage to post-production. Collaboration between cinematographers, production designers, and art directors is crucial. While digital technology offers precise control, sensitivity is still required to preserve the essence of the story being told.

The journey from a gray world to a full palette is not just a technical matter, but also about how humans convey feelings through visuals. Now, try to imagine your favorite movie scene without any color—does it still feel the same? In the world of cinema, every gradation has meaning. So, the question is: if you were in a scene today, what kind of nuances would represent your feelings?

Read more articles about the history of cinema here.