Indonesia has been familiar with film long before we began celebrating National Film Day every March 30. That date is indeed significant—it marks the start of filming for Darah dan Doa (Blood and Prayer, 1950) by Usmar Ismail. However, the journey of cinema in the archipelago actually began much earlier, when the first movie screens lit up the darkness of Batavia’s nights. Initially an exclusive form of entertainment for the European elite during the colonial era, film gradually found its way into the hearts of the Indonesian people. From trembling silent images, war propaganda, to the emergence of a national cinematic identity—its story has never been simple, but it has always been rich in color.

The First Footprints in the Colonial Era

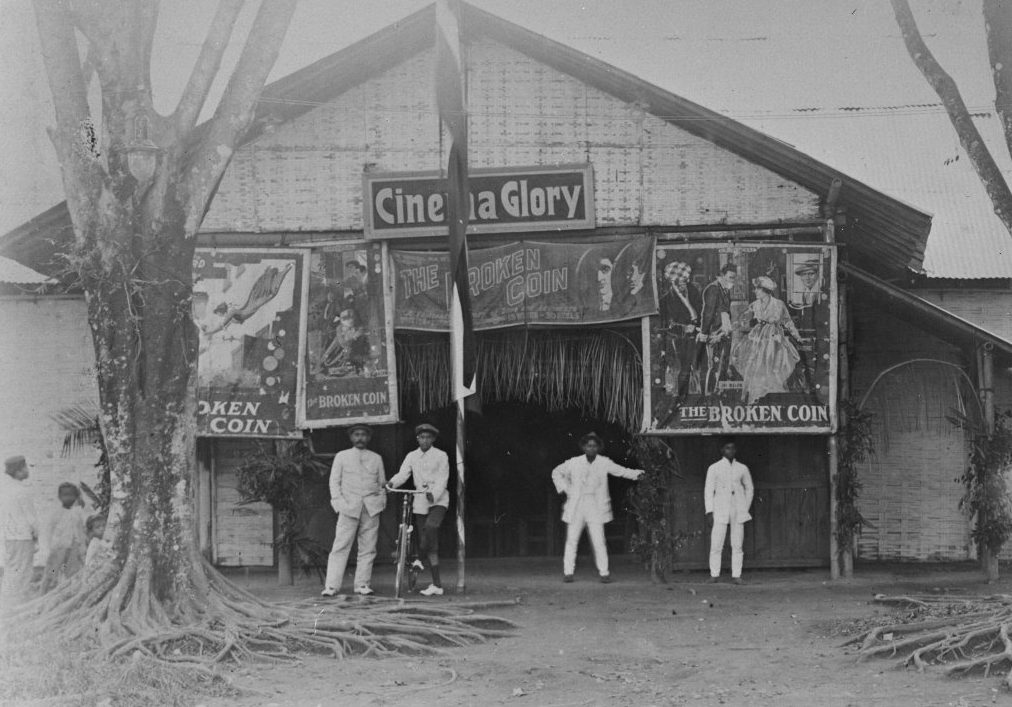

The early 20th century marked the arrival of cinema in the Dutch East Indies. The films shown were not locally produced but rather European and American productions. Around 1900, traveling cinemas began touring various cities, presenting moving images that captivated audiences. Soon after, the first permanent cinema, named Gambar Idoep, was opened in the Tanah Abang area by a Chinese-Peranakan businessman. However, access was still very limited. Watching films at the time was a luxury: expensive tickets, flickering screens, and image quality far from perfect. Yet despite these limitations, cinemas became a new window to the world, and public curiosity began to grow.

The first local film was produced in 1926 by a Dutch director who adapted a Sundanese folk tale into the silent film Loetoeng Kasaroeng. The arrival of talkies followed around 1931, including Boenga Roos from Tjikembang by The Teng Chun—a Chinese-born director who became a pioneer of indigenous cinema. The world of cinema moved quickly.

In the mid-1930s, Dutch journalist Albert Balink collaborated with Wong Bersaudara to produce big-budget films such as Pareh (1936) and Terang Boelan (1937). Thanks to local cultural influences, kroncong music accompaniment, and improved image quality, these films began to attract indigenous audiences.

A Dark Period Under Japanese Occupation

When Japan occupied the Dutch East Indies in 1942, the film industry nearly collapsed. Cinemas were turned into tools of military propaganda: war news and Japanese-produced films were mandatory screenings across the cinema network. Local studios were closed, film workers were disbanded, and only a handful of people were forced to continue working within the confines of propaganda. Japanese-made films at the time were costly to produce but lacked aesthetic and narrative substance. This period marked one of the lowest points in Indonesian cinema history, with screens remaining dark for longer than usual.

A New Dawn After Independence

Cinema screens once again shone brightly after independence was proclaimed. A significant milestone occurred on March 30, 1950, when Usmar Ismail—later known as the Father of Indonesian Cinema—began filming Darah dan Doa (Blood and Prayer). This film was not only about the struggles of soldiers but also about the struggle to build a truly “Indonesian” national cinema. This marked the beginning of the rise of local film identity, and since then, the date has been commemorated as National Film Day.

Shortly thereafter, cinema owners established the PBBSI (Indonesian Cinema Owners Association) to strengthen the distribution of national films. Support from the government and film enthusiasts produced important works such as Lewat Djam Malam (1954) by Wim Umboh and Tiga Dara (1956) by Usmar Ismail. However, political dynamics also influenced the screen. The Guided Democracy era of the 1960s led to stricter control over film themes. Strict censorship was enforced, and political issues became either fuel or constraints for film narratives.

From Glory to Decline

The 1970s–1980s are considered the golden age of Indonesian cinema. Local films proliferated, actors and actresses became icons, and television began to rebroadcast cinematic works. On the other hand, the popularity of television and the emergence of videotapes gradually eroded cinema audiences. Despite this, legendary films continued to emerge, such as Pengabdi Setan (1980) and Si Doel Anak Sekolahan (1980).

However, by the late 1990s, the film industry was hit hard by the 1997–1998 Asian economic crisis. Production stalled, many cinemas closed, and the public increasingly opted for television shows or foreign films. Indonesian cinema entered a dormant phase—a quiet period that sparked a longing for stories from its own soil.

The Indonesian cinema has come a long way—from the roar of silent projectors during the colonial era, the silence of the occupation, to the buzz of big films after independence. However, this journey is not over yet. What happened after the dormant period in the late 1990s? How did a new generation of filmmakers revive national cinema to the point where it could compete at international festivals? Behind the scenes of the increasingly digital and dynamic modern industry, there is another story waiting to be uncovered.

Stay tuned—because the most surprising part may just begin in the era closest to us. Check out the latest article here.